New Directors, Short Films

Reviewing the experimental short films of the New Directors/New Films festival.

If you’re looking for innovative works that push the bounds of cinema in a digestible package, might I suggest the short films playing at New Directors/New Films. (The brevity usually enforces clarity.) There are two separate sets of short films at this year’s ND/NF, and you can feel the not so invisible hand of curation through the clear thematic linkages within each group.

Before diving in, I want to give a quick shout out to two feature-length films that I screened in advance of their ND/NF bows: No Sleep Till (one more screening on April 11) and Sad Jokes (plays April 11 & 12). I really dug both of these films but I’m still working on my reviews and will get those up next (an evergreen statement on my part). For now, just take me at my word that if you happen to be free on Friday (and are in New York), you can have a great double bill at the Walter Reade.

Shorts Program I

Screens April 9 & 10.

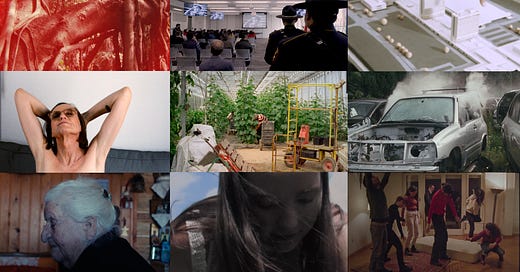

The first shorts program offers global views of migration and displacement.

Landscapes of Longing is the most abstract invocation of this theme: through three generations of her family, Anoushka Mirchandani, co-directing with Alisha Tejpal and Mireya Martinez, explores the ongoing legacy of India’s partition by intertwining the examination of artifacts and satellite imagery with first-person testimonies. The associative structure, with captions silently quoting from various texts as a counterpoint, makes this more of an art piece than a straightforward documentary.

The current wave of migration from Latin America to the United States is the backdrop for You Can’t See It From Here (No se ve desde acá), by Enrique Pedráza-Botero. Miami has long been a landing spot for Spanish-speaking arrivals, who are typically associated with displaced families fleeing poverty and unrest. But in response to the ascension of left-wing politics in countries like Colombia, wealthy expats are starting to buy luxury condos in The 305, as second, third, and even fourth homes — people and capital are both flowing northward. Pedráza-Botero contrasts this high-priced real estate with the charities and support networks that provide the less fortunate with food, clothing, and shelter. The film’s last scene is a rebuttal to nativism: Latino immigrants are making American interment flags, meant to be draped over the caskets of fallen soldiers.

Designed to commemorate the 1972 Olympics, Munich’s Olympia shopping mall was largely built by “guest workers” from Italy, Yugoslavia, and Turkey. Four decades later, it was the site of a mass shooting by a self-proclaimed Iranian-German “Aryan” who allegedly targeted people with Turkish or Arab origins. With their film In Retrospect (Rückblickend betrachtet), Daniel Asadi Faezi and Mila Zhlutenko place this past and present in conversation, tracing the path from the construction of the mall towards this racist attack. Woven throughout are excerpts from Addressee Unknown, a 1983 film by Sohrab Shahid Saless, in which a white German woman and a Turkish architect have an affair in Munich. The only extant copy is a blurry VHS recording, shared on a Farsi Telegram channel, and the visual degradation becomes a comment on whose lived experiences are preserved in a culture’s memory. One of the shots we see from that film is of the side of a building, upon which “Germany for the Germans” is spray painted. That graffiti from over forty years ago is practically the slogan for AfD, the far-right anti-immigrant party that came second in Germany’s elections earlier this year.

Xenophobia doesn’t always manifest with violence. Sometimes it’s banal intolerance, as we see in The Inhabitants. Maureen Fazendeiro riffs on the Chantal Akerman classic News From Home to question exactly who gets to call a place home. Tranquil images of Périgny, the Parisian suburb where she grew up, are narrated with letters from her mother. A Roma community has settled in this quiet commune, and Valérie is one of the few residents to have befriended and assisted them. Although the film grain texture and pastoral still lifes have the glow of a nostalgic past, the more recent maternal missives fix us to the present. Perhaps it’s a constraint of the format, but it is curious that the film itself keeps a distance from these new arrivals.

Shorts Program II

Screens April 11 & 13.

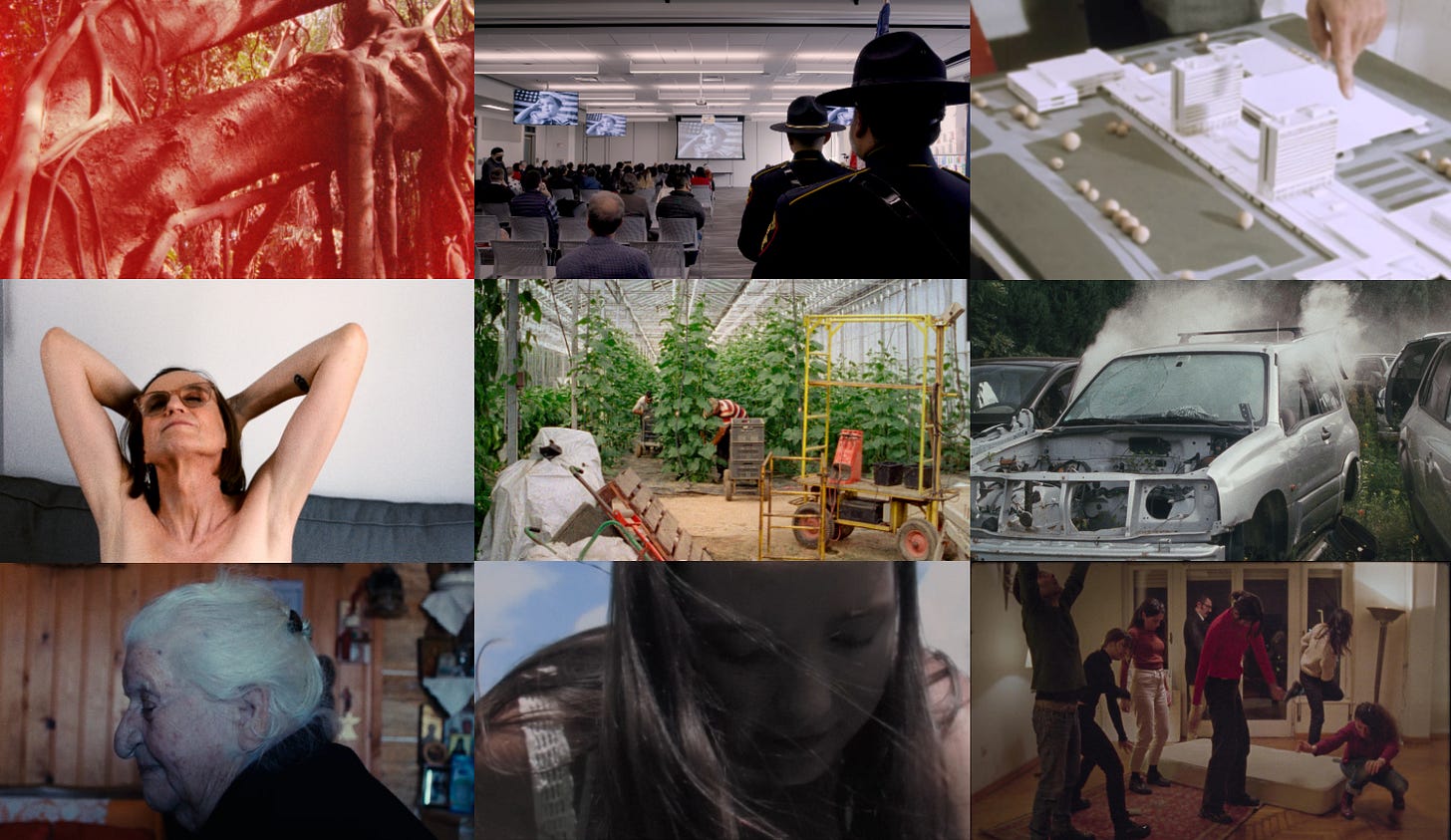

The second New Directors shorts program is largely focused on the transformation of the human body, whether it be evolution, destruction, or something in between.

In Life Story, Jessica Dunn Rovinelli applies video art stylings to what is essentially a filmed reading of a text by philosopher and media theorist McKenzie Wark. Transforming two works by Guy Debord into something of her own1, Wark muses on her gender transition and the modern fragility of life and love. As the camera glides over her nude body, an orange tint flashes on and off the screen, recalling the oscillating lights of a nightclub. It’s an abstract rave of the mind.

Thematic intentions are much clearer in Camille Vigny’s Crushed, in which metaphor allows domestic violence to be rendered without re-enactment. As the Belgian filmmaker recounts the narrative arc of a traumatic relationship, we see the setup, events, and aftermath of a demolition derby. It’s an effective juxtaposition, seeing hot rods smash into each other while listening to an account of physical abuse, the experience of dissociatively floating away from one’s body as cars are launched above the muddy earth and towards the sky. Vigny also draws our attention to the inherent misogyny of the male racers. Is it a coincidence that these cars — with names like “Hélèna” or “Chloe — are lovingly built, only to be battered, sometimes irreparably, for the thrill of it? As these vehicles are driven around in a muddy pit, men and women alike watch the destruction. “Marvel at my bruises and shudder at my smile,” proclaims the narrator. At the end of her film, Vigny describes the night she finally left her abuse with halting intimacy, paired with shots of wrecked cars sitting in permanent repose. She was able to walk away, but not everything can be repaired.

Clocking in at seven minutes, Maidenhair is the shortest of the ND/NF shorts. (It also happens to be the only pure narrative film of the bunch; the rest are some form of documentary or essay film.) While the mid-2000s setting and camcorder cinematography initially reminded me of Rap World, the aesthetic and conceptual references for director Julia Sipowicz really point to David Lynch’s Inland Empire. That film’s tagline — “A woman in trouble” — refers to Laura Dern’s character, but could equally apply to Maidenhair, minus a few decades. Young teenager Winnie is a certified horse girl and preacher’s daughter, growing up in rural Ohio. A travelling bible salesman causes her to experience an awakening of a certain kind. This immediate crush on the pimply, gangly fellow leads to a flagrantly risqué gesture during a church hymnal. (Trouble, indeed.) What follows from there is a bit murky, the formative moment of a girl’s lost naïvety submerged into the haze of digital grain.

On the volcanic Greek island of Nisyros is a village with only nine remaining inhabitants. Or eight now, because someone just passed away. The cemetery is full, so the local priest asks the villagers for permission to move the remains of their loved ones to a nearby mountain. Kevin Walker and Irene Zahariadis’s observational docu-fiction Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World feels like a decades-old artifact. The 16mm film is presented without the usual corrections made with digital scans: the dust marks are left in, the wobbly gate weave isn’t stabilized, and the subtitles have an analog “burned in” appearance. Combined with the knowledge that this was shot in 2024, not 1984, the film doesn’t have an air of timelessness, but rather that of stasis.

We shift from one of Greece’s most remote villages to its most populous city in What We Ask of a Statue Is That It Doesn’t Move, a playful exploration of antiquity and its discontents. Freely switching between vérité, man on the street interviews, and even an unostentatious musical number, director Daphné Hérétakis follows a movement of young Athenians with an intentionally provocative mission: to blow up the Parthenon. They’re taking up the charge of obscure writer Yorgos Makris, who in 1944 declared that destroying the Parthenon was the only way to subject it to “true eternity.” Random passersby are asked if they would support blowing up the temple, and they stare at the camera with bemusement. Hérétakis demonstrates two impossibilities: that of demolishing a UNESCO World Heritage site, and of making a film that encapsulates the entirety of Greece’s troubled past and its stagnant present.

In case you missed it, my previous capsule reviews of other ND/NF titles (Familiar Touch, Kyuka Before Summer’s End, The Height of the Coconut Trees, CycleMahesh, and Holy Electricity) can be found below. The latter title premieres this weekend!

This is a process called détournement, or “copying and correcting,” which I know only because the end titles explained it. Philosophy is not my strength.