Of Cats and Dogs

Reviews of Flow, Nightbitch, and Nickel Boys.

Last weekend saw the release of Nightbitch, a motherhood dramedy in which Amy Adams turns into a dog, as well as the nationwide expansion of Flow, an animated film about a cat wandering through a new world. I meant to publish these reviews last week, to coincide with their releases, but life got in the way and I blew past my (self-imposed) deadline. But they’re still in theaters, and I like to think that movies have shelf lives longer than their opening weekend.

Brief words on some other movies that are currently in theaters:

Oh, Canada, Paul Schrader’s rumination on life and lies has expanded to a handful of theaters across the country. I loved it a lot, and I will have a longer review/reflection on it next week paired with a review of The Brutalist.

Moana 2 has taken the box office by storm, but it’s a pale imitation of the brilliant first movie. As Louis Peitzman muses in Vulture: “We All Owe Lin-Manuel Miranda an Apology After Moana 2.” It’s a great headline, and a great analysis of why Miranda’s songs are so great. He was only annoying because he became oversaturated.

A Real Pain is a well-sketched examination of the different kinds of pain that people whole within them, and how it is or is not expressed. Modest in ambitions, but writer-director-actor Jesse Eisenberg excels in what he set out to do. Poland has never looked prettier on screen. At my screening of the film, Eisenberg was in the audience, watching it with his kid. 🥲

Flow

Currently playing nationwide. See playdates here.

A few weeks ago, I looked out my window and saw the strangest thing: a dog and a cat, hanging out in the same backyard. The gray tabby was lounging as the canine paced around, two natural enemies content to be in each other’s presence. Peace in our time! Witnessing this interspecies rapport was good preparation for the evening, when I watched a movie about a skittish cat who teams up with a dog (and animals of other species) to survive an environmental apocalypse.

When we first meet the feline hero of Flow, an animated movie from Latvian filmmaker Gints Zilbalodis, they are living an idyllic life in the forest. (According to the director, the characters in this movie have no gender.) The cat sleeps in a quaint cottage, and strewn about the woods are sculptures of cats (perhaps of this particular cat). Some of those statues are small wood carvings, others are giant and made of stone, as if placed there by an unseen God. Tranquility is interrupted by a sudden tsunami, and the forest disappears under the sea. (This great flood is perhaps an unconscious reference to the one in Roland Emmerich’s 2012.) Contending with a swiftly rising tide, the cat moves to higher and higher ground, eventually making it onto a boat. After a series of humorous encounters, the ark plays host to an aloof capybara, a kleptomaniac lemur, a wizened secretarybird, and a loyal golden retriever. This motley crew slowly learns to live and work with one another, as they contend with this climate catastrophe.

In the absence of any human characters, it’s remarkable how much the animals in Flow behaved like actual animals. Any anthropomorphism perceived by the viewer is merely a projection. No one speaks to each other — the entire film is dialogue-free — and instinct dictates action. The cat, noticing the lemur’s dangling tail, pounces on it, and is then distracted by a beam of light reflected from a mirror. The realistic character movements were painstakingly animated by hand (you can’t really put a motion-capture suit on a cat), and the effort pays off. As a cat dad, I can say that they nailed the feline micro-movements. That commitment to animals being animals gives Flow much of its charm, along with its handmade sensibility. Most animated films are made with a team of hundreds; this one was made with a much smaller group, and Zilbalodis wore many hats, writing, directing, editing his film, along with composing its score alongside Rihards Zalupe.

But as the film flows on, the characters start to take on more human mannerisms. Are these animals rapidly evolving in this environmental crucible, or is Zilbalodis cheating his initial conceit to fulfill his narrative? What initially seems like an inspired setting devolves into a hodge-podge of references, ranging from Percy Bysshe Shelley’s “Ozymandias” to video games like Myst or Shadow of the Colossus. The cel-shaded animation and wordless narrative often makes Flow feel like you’re watching a Let’s Play of an open-world platformer, so much so that I was surprised that the movie was not made in Unreal Engine. (The team used Blender, which was originally developed game design software but is now solely focused on motion graphics.)

Every movie, whether a neo-realist drama or a sci-fi fantasy, has to build its own world, and a good director will implicitly communicate the rules of that world to the viewer. I realized a bit too late that Flow was not meant to be taken so literally — that it was a fable — but I’m not sure if Zilbalodis ably communicated that earlier in the film. Too late into the runtime, the filmmaker upends expectations of what his characters are capable of, and what can seem like whimsy to some can come off as contrivance to others.

★★★☆☆

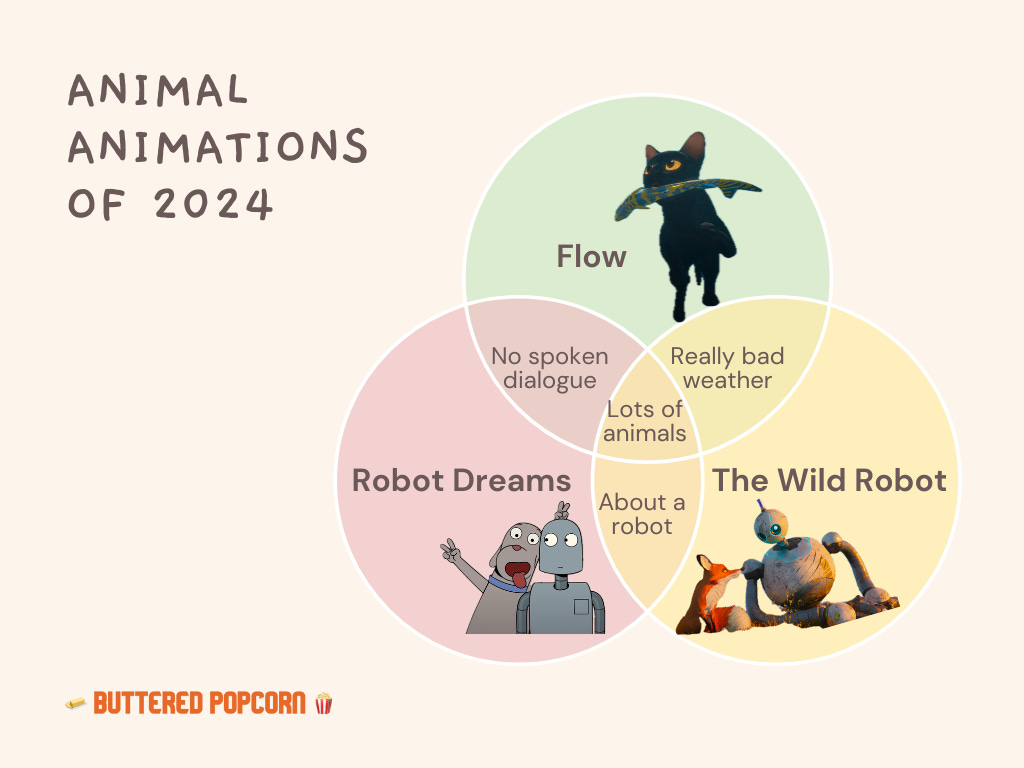

A Venn Diagram

Funny enough, this is not the first 2024 animated film to be about animals contending with an environmental catastrophe, nor is it the first animated movie this year with animal protagonists to be dialogue-free. Here is a comparison between Flow, Robot Dreams, and The Wild Robot.

The time KitKat encountered a dog

My cat had not interacted with a dog since being rescued until last year, when Dorothy and Lester were visiting New York. They were dogsitting for a friend here, and after being assured that he was very polite, they brought the pup over to my place. The dog was super friendly, was used to being around cats, and didn’t bark once. KitKat was not happy at first, hissing at the dog and generally keeping her distance, but by the end of the night, the two were sharing the couch. They were on opposite ends, but hooray for tolerance!

Nightbitch

Currently in limited release.

Interspecies relations don’t go nearly so well in Nightbitch. Ten years into her directing career, Marielle Heller has established herself as a filmmaker who displays a keen empathy for her flawed protagonists. Whether it’s the fifteen-year-old sleeping with her mother’s boyfriend in The Diary of a Teenage Girl, Melissa McCarthy’s irascible literary forger in Can You Ever Forgive Me?, or a cynical journalist trying to take down Mr. Rogers (played by Tom Hanks himself!) in A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood — all are complex characters within an accessible story. Heller also directed the pro-shot of Heidi Schreck’s terrific play What the Constitution Means to Me, in which she seems to know, in every scene, exactly where the camera should be placed for maximum impact.

The names of those four films are quite long. Perhaps it’s a coincidence, but the brevity of the title for Heller’s newest project, Nightbitch, may have broken the director’s winning streak. It’s never a good sign when a movie is being released two years after it was shot and then dumped in theaters. The film opened on just 82 screens and the studio is not reporting box office grosses. Translation: this dog is being put down.

When we meet the unnamed Mother at the center of this film (played by Amy Adams), she is not having a good time. She’s an artist who hung up her paintbrushes in order to raise her son somewhere in suburbia. Her husband (Scoot McNairy) is out of the picture during the workweek, constantly traveling for some vaguely defined job. On the weekends, he needs just as much caring for as the kiddo, and needless to say, the marriage gets rocky. The undignifying routine of stay at home motherhood starts to break her down: English muffins in the morning, mommy and me music classes at the library, cleaning, cleaning, constantly cleaning. Her art school friends are still in the city, living lives far removed from her own. She’s repelled by the seemingly enthusiastic moms in the suburbs. For reasons too convoluted to get into in this review, the Mother discovers that she is slowly transforming into a dog, and starts prowling the streets after dark, thereby becoming the titular Nightbitch.

Dogged with bizarre tonal shifts and blunt messaging, Nightbitch already has the dubious distinction of being Heller’s least beloved film. Misbegotten as it may be, this is also her most personal work yet. All of her movies, including this one, have been adapted from a book or a magazine article. But this film is heavily influenced by its director’s own experience as a new mother, trying desperately to balance her family with her career1. The dog transforming thing doesn’t interest Heller much; it’s treated merely as a flight of fantasy. The real meat on this bone is in her figuring out how to live a life both as a mother and a woman. In its best scenes, Nightbitch gets to the raw, bestial emotions that every new mother endures when making such tradeoffs. It’s also a movie that explores American parenthood as a uniquely burdensome phenomenon. Thanks to barely any government support, this is a country where it’s insanely expensive to raise a child, and starting a family often means ending a career if you can’t afford a nanny.

It all works out in the end, as it does in most movies. The fictional Mother and the Husband repair their marriage. They divide parental responsibilities, which affords the Mother with the time to make art again. (The film suggests that if being a mother is a job — and it is — then moms should get benefits and PTO.) But it was a struggle to get to that ending, and the real life mother of two kids made a movie about just that.

★★★☆☆

Nickel Boys

Currently playing in New York. Opens in LA on December 20, with nationwide expansion in January.

(This review is republished from my New York Film Festival coverage, with minor edits. If you want to get the skinny about the unique first-person perspective, check out this interview in The Verge.)

Innovative and artful while staying within the bounds of the mainstream, Nickel Boys is a brilliantly conceived adaptation of Colson Whitehead’s Pulitzer-winning novel. The story tracks the friendship between two young Black boys who meet at a segregated reform school in the Jim Crow South, and the decades-spanning reverberations from the horrific abuse inflicted upon them by the school’s superiors. Director RaMell Ross brings us inside the perspectives of Elwood and Turner: every shot in this movie is from one of their points of view, and usually in the first person. (Scenes with an older Elwood show the back of his head.) It’s not as avant-garde as it seems; you pretty quickly get the hang of the cinematic language. Ross establishes the rules of this movie’s world, and shows you how to immerse yourself within it.

With actors operating cameras and camera operators standing in for actors, the first person shots could have been a gimmick, akin to projecting an Oculus Rift video game onto a cinema screen. But cinematographer Jomo Fray utilizes a shallow focus and a roving camera that brings the viewer into the character’s subjective experience. It was painful once I realized that we never got a good view of the white authority figures — the cop, the headmaster, and so on — because Elwood had to keep his head down.

The first person perspective also avoids us from having to see exploitative imagery of racial violence. In a way, that makes these scenes harder to watch. We’re not looking at Elwood being brutalized, we are seeing what Elwood is seeing while it’s happening. It’s especially wrenching with the context that the novel was inspired by true events: there was an actual school in Florida that only recently exhumed the bodies of children who were killed there. Many of the bodies remain unidentified, their stories forever unknown. Ross, the film’s director, cited Saidiya Hartman’s concept of “critical fabulation” as a key inspiration when putting the script together with co-writer Joslyn Barnes. Where both Whitehead and Ross step in with Nickel Boys is to create a fictional story that can speak to the truth of what happened at that school — and many other places like it — in the absence of historical record.

On its own, the story is strong enough to make a conventionally conceived movie adaptation. But in addition to the point of view cinematography, Ross, who until now has worked in documentary films and photography, also employs the language of non-fiction filmmaking to deepen the material. In between some scenes, there are clips of archival footage spanning the twentieth century. There’s a particular focus on the Space Race, which was heating up in 1968, when this film is set. Early in the film, we see Elwood is especially interested in astronomy, and at one point we see an image of our planet. “The view of Earth from 240,000 miles in space,” intones the narrator. After experiencing Elwood’s world from 240 millimeters away, it becomes clear why he has such a fascination with how to escape it.

Nickel Academy has both white and Black children, but they are segregated. When the populations do interact, the racial hierarchy takes precedence over any potential class or youth solidarity. Interspersed throughout Nickel Boys are clips from The Defiant Ones, a landmark classic in which Sidney Poitier and Tony Curtis are escaped convicts who must befriend each other to survive. But that movie, which was released in 1958, was a Hollywood fantasy. Such a friendship between white and Black might have been possible in California, or here in New York. But not in Florida, even ten years after that picture premiered. Not then.

★★★★½

Emily Nussbaum’s excellent profile in The New Yorker gets into the details on this.

Love that you have watermarked Buttered Popcorn images now. (Referring to the Venn diagram)