A Christmas Bounty at the Cinema

A few words about Babygirl, The Fire Inside, Mufasa, Vermiglio, and The Room Next Door.

Merry Christmas Eve, everyone! There’s a lot of films opening this week, big and small, so I’ve put together some brief thoughts on the ones I’ve already seen. (Babygirl, which is the only new release that could feasibly be called a Christmas movie, gets a longer review.) I haven’t watched the two biggest Christmas releases, but I hear from friends that A Complete Unknown and Nosferatu are pretty much what you’d expect. One is a recounting of Bob Dylan’s early career that is well-made, but not quite invigorating. The other is Robert Eggers doing his thing with one of cinema’s oldest vampire tales. I’m looking forward to seeing both within the next couple weeks.

If you’re in New York or LA, The Brutalist has begun its limited engagement, with many screenings projected on 70mm film. (It’ll expand nationwide in January, presumably after it racks up a bunch of Oscar nominations). I’ve been working on a twinned review of that film and Paul Schrader’s Oh, Canada, but it’s been a tough nut to crack, so I’ll publish the piece early next year. My angle on it makes more sense once you’ve actually seen the movie.

But if you’re not trying to leave the house (understandable; it is very cold where I am), I might recommend Christmas Eve at Miller’s Point, which is available to rent or streaming on AMC+. (I don’t know a single person who subscribes to AMC+.) I just watched it on Sunday. Set in a fictional town on Long Island, Tyler Taormina’s film immerses us in a large Italian family’s Christmas Eve party. Michael Cera, Francesca Scorsese, and a few other recognizable faces make charming appearances within the cast of otherwise mostly unknown actors. Full of clear-eyed nostalgia tinged with melancholy, it’s my kind of Christmas movie. The fairly experimental narrative and surreal tone will frustrate some viewers, but I was utterly captivated.

Babygirl

Not the first time that Nicole Kidman has starred in a yuletide erotic drama set in New York, and Babygirl could be viewed as director Halina Reijn’s feminist response to Eyes Wide Shut. This time around, Kidman gets to be the one desperately walking the streets of Manhattan, as Tom Cruise had done in Stanley Kubrick’s masterpiece. In this film, our dubiously ethic’d1 heroine is Romy, the CEO of a robotics company. Immaculately dressed, she maintains a regal presence within her gleaming office in midtown Manhattan2. But the Boss Babygirl finds herself flustered by Samuel (Harris Dickinson), an intern whose baby face and tender attentiveness belies a thrillingly domineering demeanor.

The two edge their way towards an affair, with the roles of power and control inverted from their workplace relationship. Kidman’s bracing performance reveals Romy as a woman repulsed by her desires, corseted by America’s puritanical morals. Dickinson is a more than capable scene partner. We’re never quite sure what Samuel’s game is, but we know that he knows what he’s doing. And the rare occasions when his mask of control slips off are genuinely frightening. Aside from such moments, this is a much funnier movie than one might expect. It’s less of an erotic thriller, and more of an erotic comedy, where the humor is as dry as Romy is wet during those after hours encounters. You’ll never look at a glass of milk the same way again.

This film rides the wave of several recent movies in which a middle-aged woman has sexual relations with a much younger man. But what sets Babygirl apart from the likes of The Idea of You or May December — besides the sex scenes — is the key presence of Romy’s husband Samuel (Antonio Banderas). He’s equally successful in his career as a theater director. When the film begins, he’s in rehearsals for a production of Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler, a play similarly about a woman feeling unfulfilled in her marriage3. The only thing is that the man is too vanilla in bed, leaving Romy’s fantasies unrealized in an otherwise happy relationship. As the affair between Romy and Samuel gets riskier (and friskier), one unexpectedly starts feeling bad for the poor husband, especially during the shattering climax.

But once the fantasy is over, Reijn’s intentions behind her film become clearer. Babygirl, despite being part of a current microtrend of feminist age gap romances, reveals itself to be one of the oldest kinds of Hollywood stories: the comedy of remarriage. The lovers to enemies to lovers pipeline was a popular template during the late 1930s and early 1940s, just after the imposition of the restrictive Hays Code. (Most of them starred Cary Grant.) Hemmed in by Catholic morality standards, pictures like The Awful Truth and The Philadelphia Story managed to make a proto-feminist statement, advocating for a matrimony formed by love, not for economic or social convenience. But they all wind up getting the feuding couple back together again. In its 21st century update, Babygirl may add a bit of kink, but the otherwise traditionalist message remains.

⭑⭑⭑⭑☆

Should you watch this with your parents? Only if you are questionably close with them.

Food pairing: cookies and milk. Very Santa coded! Santa Babygirl?

The Fire Inside

This true story sports drama, about Olympic boxer Claressa Shields (Ryan Destiny), initially appears to be an inspirational but basic tale of rags to riches. In 2006, the native of Flint, Michigan came under the tutelage of local coach Jason Crutchfield (Brian Tyree Henry), eventually making her way to the London Games at the age of seventeen. Despite societal and financial barriers — Claressa is a Black woman from a poor family — she earns a Gold Medal, her wildest dreams realized.

During the first half of The Fire Inside (which originally had the much better title Flint Strong), I wondered when screenwriter Barry Jenkins and director Rachel Morrison would make this project more interesting. The journey to the Olympics is rousing, but we’ve seen this film before. I even wondered if the film was partially funded by the IOC. But the meat of the story is what happens after Claressa wins the Gold and the Olympic bubble bursts. The promised riches never come; brands and sponsors shy away from the young woman who tells journalists that she likes “hitting people and making them cry.” It exposes a double standard for boxers: men can be bullies, in and out of the ring, but women must be demure when the gloves come off. Despite the modest start, the film subverts its form. But it doesn’t stay there too long; Claressa refuses to be an anti-hero, realizing her hometown desperately needs someone to look up to, and determined to succeed when the world counts her out. She’s got the eye of the tiger.

Morrison, a cinematographer stepping into the director’s chair for the first time, shoots the boxing matches adequately, but without the intensity or precision of the best films in the genre. Her direction better suits the film’s more intimate scenes, which are also an example of how great cinematography need not be flashy. (The film is lensed by Rina Yang, who has also shot a handful of Taylor Swift’s music videos.) The water crisis is hinted at; we see the water towers looming in the background. But The Fire Inside passionately makes the case that a city — and a person — should be known for more than just its struggles. Flint has heroes, too.

⭑⭑⭑½☆

Should you watch this with your parents? This is suitable for the whole family, old fashioned studio fare that we used to see more of in the recent past.

Mufasa: The Lion King

That title card saying "A Film by Barry Jenkins" is someone’s idea of a sick joke. The director who made Moonlight and If Beale Street Could Talk took on a Disney project, a prequel to the unnecessary animated remake of The Lion King. There is a certain set of skills required to make a movie at this scale, but neither he nor his frequent collaborators possess them. (Even he kind of thinks so, if you read between the lines of this profile from Matt Zoller Seitz on this film’s production. Choice quote: “[Virtual production] is not my thing. I want to work the other way again, where I want to physically get everything there.”)

The closeups and long takes that define Jenkins’s other films just completely fail here. It’s suffocating for the “camera” to be inches from a fake lion whose face can’t properly emote. The editing is just awfully paced too, moving things right along from scene to scene without being able to sit within a moment. Because we too easily see the machinery of the screenplay from Jeff Nathanson, there’s no connection between the viewer and these animal characters. And because of that, when the musical sequences kick in, the songs don’t achieve their desired impact. That’s too bad, because Lin-Manuel Miranda wrote some decent tunes here, though he relies too much on a point-counterpoint lyric in the duets. While he's kinda phoning it in on some songs, it’s not like he had much to work with.

One other baffling thing about Mufasa: Aaron Pierre, a British actor, voices a character with an American accent. Kelvin Harrison Jr., who is American, voices a character with a British accent. They can speak just fine, but the accents fall apart when they’re singing. They could have swapped roles.

⭑½☆☆☆

Should you watch this with your parents? Only if you hate them almost as much as you hate yourself.

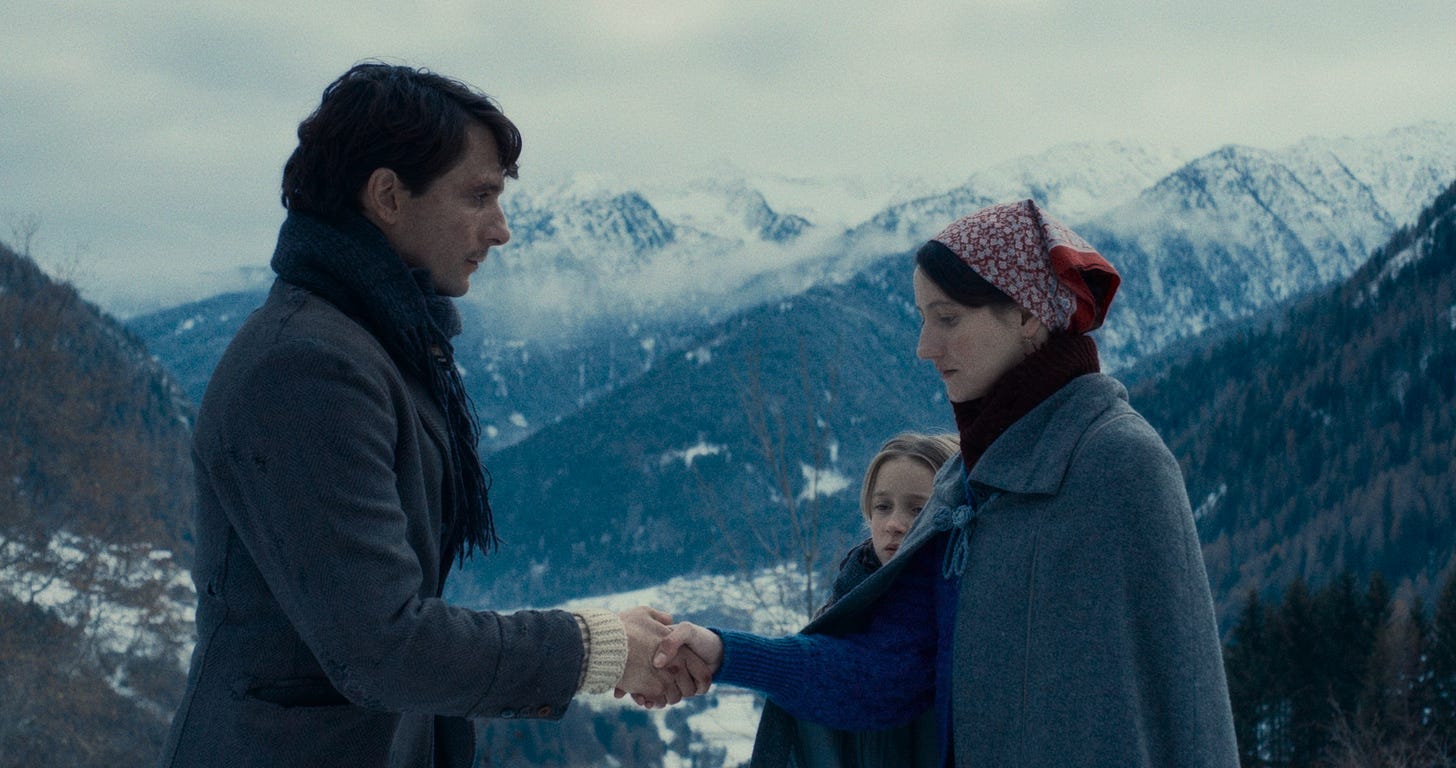

Vermiglio

A portrait of an unraveling family in the Italian Alps, during the waning days of World War II. The mountains are breathtaking to behold, but the vignette style of narrative, inspired by director Maura Delpero’s own family history, isn’t as transfixing until a failed romance between the eldest daughter (Martina Scrinzi) and an army deserter (Giuseppe De Domenico) takes control of the story.

⭑⭑⭑☆☆

Should you watch this with your parents? Unless they usually frequent the arthouse, this will put them to sleep.

The Room Next Door

(Republished, with minor edits, from my prior NYFF coverage.)

It took fifty years for Pedro Almodóvar to make his first English-language feature film, and hopefully it won’t be long until the next. Based on a novel by Sigrid Nunez, this affecting drama touches on coming to terms with mortality (timeless!) and making sense of the impending climate catastrophe (timely!). The Spanish director has long since moved on from the exuberant, campy style of his best-known work. But the classic Almodóvar hallmarks remain: female protagonists, immaculately designed homes, a score composed by Alberto Iglesias, the color red being everywhere.

Julianne Moore and Tilda Swinton make for a formidable pair, as old friends brought back together after the latter makes a strange request. John Turturro shows up for about ten minutes to flirt with Moore and rant about the climate crisis, which is super fun. The delivery of dialogue can feel rather stilted, but Spanish-speaking friends of mine have said that Almodóvar’s movies in his native language are similar. In her Actors on Actors conversation, Swinton said that they speak “Almodóvarian.”

Swinton wears many great outfits, but I particularly need the sweater she wears during an all-night movie marathon. She and Moore watch Buster Keaton’s Seven Chances, Max Ophüls’ Letter from an Unknown Woman, and John Huston’s adaptation of The Dead. That James Joyce story is quoted multiple times in the movie, and could be good prep for seeing this film.

If you’ve seen this, you’re probably wondering if it’s possible to stay in the beautiful, brutalist upstate home that Moore and Swinton rent for a month. Unfortunately, Casa Szoke is an hour outside of Madrid, and appears to be a private residence. It is much easier to visit the film’s Manhattan locations. The very first scene is at the Rizzoli bookstore next to Madison Square Park, and one scene was filmed in the lobby of Alice Tully Hall, a tribute from Almodóvar to NYFF.

⭑⭑⭑⭑☆

Should you watch this with your parents? Depends on what they’re into, but I think my mom would like it.

I am aware I am making up a word that doesn’t exist.

If you want to see Tensile Automation’s building, head over to 1245 Broadway, on the intersection of 31st Street. A couple other prominent New York locations are cocktail bar The Nines and rave haven Knockdown Center/Basement.

Samuel’s extensive use of video walls are an homage to Ivo van Hove, whose theater company Reijn had been a part of for many years during her previous career as a stage actress.